THE HAUNTED WOOD BY SAM LEITH - A History of Childhood Reading

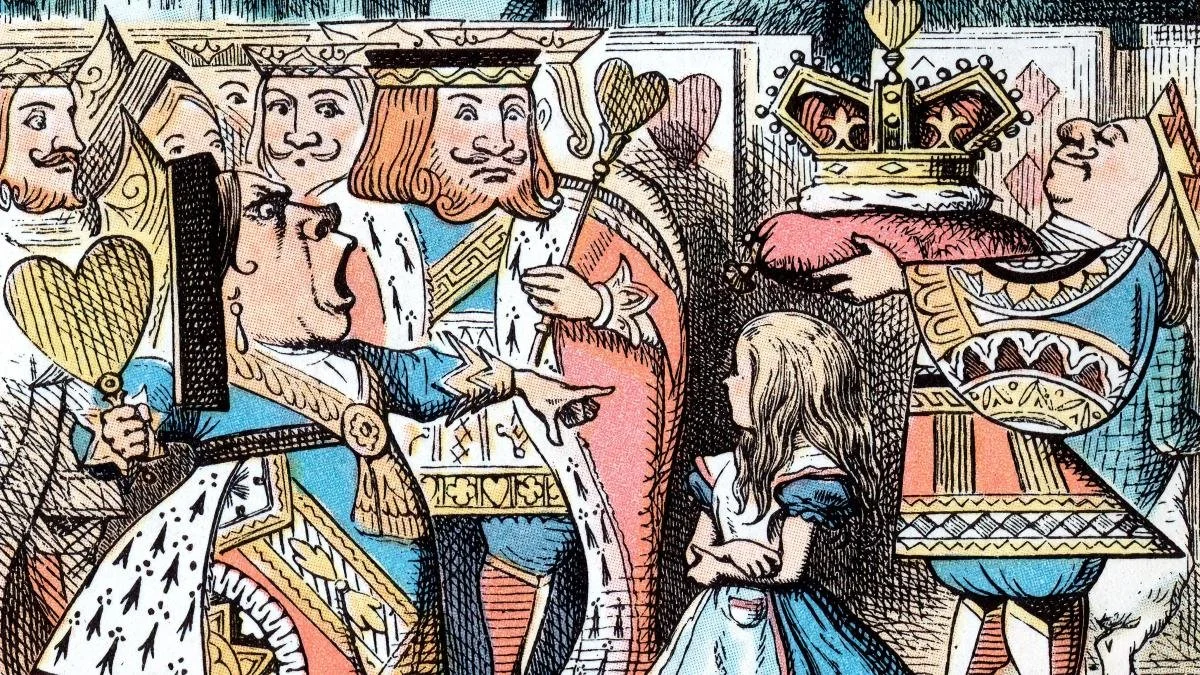

Alice in Wonderland

Sometimes a book appears, destined to be a classic. The Haunted Wood is so dense, so detailed and so packed with amazing insight it simply captivates the imagination – even as you boggle at the sheer brilliance of the whole project.

Sam Leith begins with an in-depth look at childhood itself and he tackles some of the harsher theories of how parents felt towards their offspring. Sociologists like Lawrence Stone in the 1970s claimed parents were flinty hearted impervious to the loss of babies in a world where so many died young. But Leith strikes back with his own evidence of the tenderness and heartbreak such bereavements brought – remember such sad epitaphs as Ben Jonson’s short ode to his five year old “Here lies Ben Jonson , his best work’

But life for most children in the past was harsh. They worked for their living ‘When Daniel Defoe toured England in the early eighteenth century, he reported approvingly from Norfolk that ‘the very children after four or five years of age, could every one earn their own bread’. But by the end of that century, our author remarks ‘the grimness of some of that bread-earning came to public attention.’ In 1766 Hanway’s An Earnest Appeal for Mercy to the Children of the Poor pleaded we should at least make it nicer for them’ and make labour as pleasant as possible and ‘with a tender regard to the measure of a young person’s strength of body and mind’ . Yet the industrial evolution helped to create children the ‘white slaves’ of the new factories . A Yorkshireman Richard Oastler petitioned Parliament that ‘The children of the poor are treated with a rigour unheard of in the barbarous regions and are absolutely, sometimes, worked to death’.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘campaigned for an Act of Parliament to protect children’ and saw the parallel with the oppression of the Black races’ our poor little White slaves the children in our cotton Factories’. In fact William Blake wrote in Songs of Innocence ,of much oppressed chimney sweeps. ‘The poem presents a dream of ‘thousands of sweepers all of them lock’d up in coffins of black’ where they worked and slept.’ Almost a century later when Charles Kingsley wrote The Water - Babies, a book that did for child workers what Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin did for enslaved Africans in America, public opinion and legislation forced home awareness of the suffering of so many children ‘From the Enlightenment onward, something changed. And the change to place both in the realm of ideas and in the shape of day-to-day life.’ Children’s literature in its Golden Age – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Tom Brown’s Schooldays - and the Water-Babies’ set children’s writing on the road to modernity’ our author tells us. But not before he delves into the utterly grim ways of the Puritan and Calvinist tropes of writing for children. One reading plan has a narrator, none other than ‘, Jack the Giant Killer’. In a system of pins behaviour is monitored. On one side of a cushion is black – and the other red. A child’s behaviour is measured with this system. Pins on the red side ‘mean a Penny’ But if ever the Pins be all found on the Black side then I will send a Rod and you shall be whipt’ the cheerful multi murderer tells his charges.

At the same time as these stern moralists many women, were at work with their strict lessons, Mrs Sarah Trimmer set up a school for her own twelve children in Brentford and added to it several poor villagers. An educational philanthropist ‘She captured the zeitgeist of benign class condescension, hoping to encourage cleanliness godliness and literacy in working class children and equip them for respectable lives in service” Do not tear the book. Only bad boys tear books” as Sam Leith notes ‘There’s a touch, I fancy of Joyce Grenfell in there” Fairy stories came on the scene. Perrault’s collection went into English in 1729 and the Arabian Nights in 1706. ‘even as Mrs Trimmer was about her earnest attempts to educate her charges, the world of children’s literature was about to change````````````

For all the disapproval of these stiff matrons , a ‘warm breeze from the Continent ‘ was blowing into Britain.Fairy Tales from the ‘umbrageous forests ‘the Brothers Grimm entered alongside Perrault’s nursery tales and most daring of all The Thousand and One Nights. Initially these weren’t for children they were folk collections later pared down to children’s stories in 1825. Sam Leith chronicles the story of Cinderella – the story begins in China in the early 800s who does go to the Ball. But in a later version Zezerolla is persuaded by the Fairy Godmother a sewing mistress - figure to finsish off her stepmother by slamming the lid of a chest shut on her head. It is a long wayfrom the Disney version where virtue triumphs. And the Grimm version has been quietly suppressed. It does not fit at all with what we feel children should experience. Hans Christian Andersen revived folk tales and made up his own stories. His work was to go from Copenhagen round the world – it is revered in India and China. And it lives on most recently the Snow Queen as Frozen for Disney. Typically of this amazingly detailed book , we find out what a strange character Andersen was . He stayed with Charles Dickens for three weeks longer than planned ‘we are suffering very much from Anderson’ he wrote as if the visitor were a disease – he was ungainly and Elizabeth Barret Browning said he was like his own ugly duck, and never fitted in .But ‘fantasies of escape and transformation’ were in the stories from Arabian Nights his father read to him. Again, Sam Leith leads the reader into a mini biography of this remarkable grotesquely featured phenomenon. Like so much in this gloriously detailed volume, each storyteller has his own even more remarkable tale to tell.

He makes brilliant work of Charles Kingsley that other Victorian writer – but reflects that if we really knew the understory of the Water-Babies it would not survive as a cute pantomime playful subject for Christmas.

The chapters on Alice in Wonderland are a treatise and historical analysis of their own, where Sam Leith explore the lonely life of the Reverend Dodson, and the nuance of so much of Alice’s true adventures, on and off the page. He moves from the book’s origin to its appearance in a Jeferson Airplanes number and in between most interestingly speculates on the psychology of children, their astonishing minds.

The most intriguing parts of the book involve the great writers of the Edwardian age.E.Nesbit author of The Railway Children and The Treasure seekers might lay claim to closest a writer has come to an understanding the minds of her readers. And she does it with one single faculty, the ability to recall what childhood felt like ’Only by remembering how you felt and thought when you yourself were a child can you arrive at any understanding of the thoughts and feelings of children.’ She shares this gift with Francis Hodgson Burnett, the author of the market -storming Little Lord Fauntleroy, a novel that sold out in American and spread merch like no other. Every little boy’s mother yearned for him to have a floppy black velvet suit lace collar and long curly blonde locks. It made the author rich.She went on to write The Little Princess and the fascinating ‘Secret Garden’, valued today as classic works. J.K Rowling has this same gift, in a deep dive into her life and work, Leith shows how she can imagine her life as a child between 11 and 18 in amazing detail.

And amazing detail is what Sam Leith’s work presents. It is a brilliant tour des horizons of all children’s books and whilst he reveals their authors in true life minutiae, he also shows the adult reader what they might have missed in their childhoods, makes it live and brings a new scholarly but journalistic flair to the entire oeuvre. A must read for children of all ages.